Ballroom

History

Ballroom

History

Ballroom

History

Living the Fantasy:

A Brief History of Baltimore Ballroom

Text by Joseph Plaster

Historians trace contemporary ballroom culture to the interracial drag balls staged in cities such as New York, Chicago, and Baltimore as early as the 1890s. The elaborate balls, George Chauncey argues, were “the largest and most significant collective events of gay society” in the early twentieth century. In a world hostile to queer people, “the balls confirmed their numbers by bringing thousands together. In a world that disparaged their culture, it was at the drag balls, more than any place else, that the gay world saw itself, celebrated itself, and affirmed itself.” In the 1940s, poet and novelist Langston Hughes proclaimed drag balls to be the “strangest and gaudiest of all Harlem spectacles in the 1920s,” describing them as “spectacles in colour.”

Drag balls were patterned on—but gave new meaning to—the debutante and masquerade balls of the dominant culture. The term “coming out” was an arch play on the language of women’s culture—in this case the expression used to refer to the ritual of a debutante’s formal introduction to, or “coming out” into, the society of her cultural peers. In 1931, for example, the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper announced “the coming out of new debutantes into homo-sexual society” as “the outstanding feature” of a Baltimore drag ball. Young queens wore “elaborate gowns, wraps, jewelry, [and] pumps” as they entered the city’s gay subculture.

Living the Fantasy:

A Brief History of Baltimore Ballroom

Text by Joseph Plaster

Historians trace contemporary ballroom culture to the interracial drag balls staged in cities such as New York, Chicago, and Baltimore as early as the 1890s. The elaborate balls, George Chauncey argues, were “the largest and most significant collective events of gay society” in the early twentieth century. In a world hostile to queer people, “the balls confirmed their numbers by bringing thousands together. In a world that disparaged their culture, it was at the drag balls, more than any place else, that the gay world saw itself, celebrated itself, and affirmed itself.” In the 1940s, poet and novelist Langston Hughes proclaimed drag balls to be the “strangest and gaudiest of all Harlem spectacles in the 1920s,” describing them as “spectacles in colour.”

Drag balls were patterned on—but gave new meaning to—the debutante and masquerade balls of the dominant culture. The term “coming out” was an arch play on the language of women’s culture—in this case the expression used to refer to the ritual of a debutante’s formal introduction to, or “coming out” into, the society of her cultural peers. In 1931, for example, the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper announced “the coming out of new debutantes into homo-sexual society” as “the outstanding feature” of a Baltimore drag ball. Young queens wore “elaborate gowns, wraps, jewelry, [and] pumps” as they entered the city’s gay subculture.

The pageantry of the interracial balls sometimes exacerbated racial divisions, and may have contributed to the development of contemporary ballroom culture. “The costume competition became a highly charged affair,” Chauncey argues, “with all sides watching to see whether a black or white queen would be crowned.” Some historians suggest that the anti-black bias of interracial balls in the 1960s and 1970s sparked the creation of contemporary ballroom culture. Many argue that the first “house” came into existence in Harlem in the 1970s, when Crystal LaBeija, infuriated by the anti-black bias of drag competitions, began organizing her own balls. She founded the House of LaBeija, often credited as starting the house system in ball culture.

View Crystal LaBeija in this iconic scene from Frank Simon’s “The Queen,” 1968

Contemporary ballroom culture has since the 1970s consisted of two primary features: anchoring family-like structures, called houses, and the competitive balls that they produce. “Houses” are kinship networks that are configured socially rather than biologically. In general, a “house” does not signify an actual building; rather, it represents the ways in which its members interact with each other as a family unit. Ballroom artists organize elaborate balls, competitions at which participants “walk” (i.e., compete) in categories for trophies and prizes. “The gender system and kin labor,” ballroom member and ethnographer Marlon Bailey writes, “create a close-knit community, and that community expresses its essence at these events.”

View the trailer for “Paris is Burning” (1991) the much-criticized documentary about New York City’s ball scene in the 1980s, featuring Willi Ninja, Pepper LaBeija, and Paris Dupree.

Crystal LaBeija in Frank Simon’s “The Queen,” 1968

The pageantry of the interracial balls sometimes exacerbated racial divisions, and may have contributed to the development of contemporary ballroom culture. “The costume competition became a highly charged affair,” Chauncey argues, “with all sides watching to see whether a black or white queen would be crowned.” Some historians suggest that the anti-black bias of interracial balls in the 1960s and 1970s sparked the creation of contemporary ballroom culture. Many argue that the first “house” came into existence in Harlem in the 1970s, when Crystal LaBeija, infuriated by the anti-black bias of drag competitions, began organizing her own balls. She founded the House of LaBeija, often credited as starting the house system in ball culture.

View Crystal LaBeija in this iconic scene from Frank Simon’s “The Queen,” 1968

Contemporary ballroom culture has since the 1970s consisted of two primary features: anchoring family-like structures, called houses, and the competitive balls that they produce. “Houses” are kinship networks that are configured socially rather than biologically. In general, a “house” does not signify an actual building; rather, it represents the ways in which its members interact with each other as a family unit. Ballroom artists organize elaborate balls, competitions at which participants “walk” (i.e., compete) in categories for trophies and prizes. “The gender system and kin labor,” ballroom member and ethnographer Marlon Bailey writes, “create a close-knit community, and that community expresses its essence at these events.”

View the trailer for “Paris is Burning” (1991) the much-criticized documentary about New York City’s ball scene in the 1980s, featuring Willi Ninja, Pepper LaBeija, and Paris Dupree.

Crystal LaBeija in Frank Simon’s “The Queen,” 1968

Scene from “Paris is Burning” (1991) the much-criticized documentary about New York City’s ball scene in the 1980s, featuring Willi Ninja, Pepper LaBeija, and Paris Dupree.

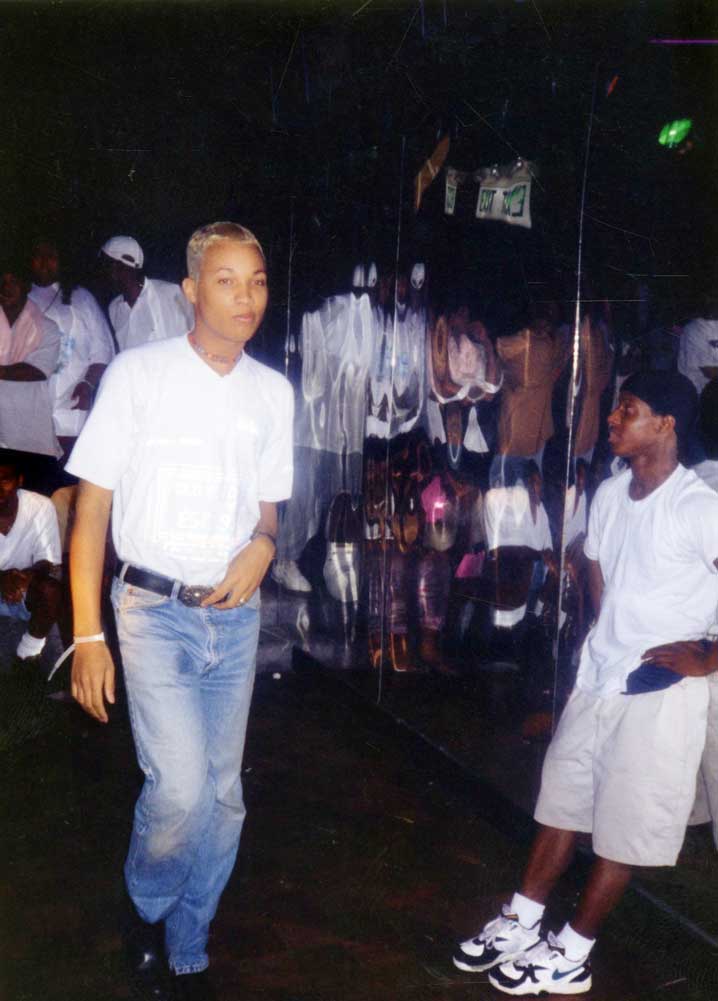

I recorded oral histories with Icons in Baltimore’s ballroom scene who told me that a few “pioneers” – among them Tony Revlon and Lisa Revlon – brought ballroom culture from New York City to Baltimore in the 1980s. Lisa Revlon told me that she founded the House of Face in New York, met pioneers like Paris Dupree, and joined the House of Revlon. Ballroom artists from New York City followed her to Baltimore in the 1980s. “We ended up bringing ‘em down here to Baltimore,” she told me, “and they liked it…They was hanging out with us. They started going to the club with us. They already knew we were Revlons.” The Revlons organized a ball at Club Fantasy, Lisa said, “so in essence, I did bring all that madness to Baltimore.”

Alvernian Davis, the founder of the Iconic House of Prestige, told me the House of Revlon “was the first house in Baltimore, even though it was a New York City house. Tony and Stewart, which were the mother and father at the time, they moved out of New York and moved to Baltimore. So they created this whole community of ballroom people down there, which mostly were Revlon members.” Enrique St. Laurent recalled, “It was [the houses of] Face, Revlon, and then other houses just kinda came in [in the 1980s]. So you had houses that were coming from New York, like Ebony. Chanel came in…Houses started coming in, filtering in Baltimore”

Sandy Dior’e told me she founded the House of Dior’e in 1995. “I was the foundation and the blueprint of that,” she said. “And it’s not just in ballroom in Baltimore city, but it’s in outreach I do; it’s in advocacy I do; it’s in helping my community.” In Baltimore, “I don’t believe there’s anyone that can contest to me not being mother or grandmother or auntie.” Monique West told me she joined the House of Dior’e around 1995. “That was the particular family that I belonged to. So it was one apartment just full of people and everybody in there were like family, helping each other get ready, helping each other get whatever they needed for a category.” There were “about 15 people in a one-bedroom apartment,” she recalled. “Everybody was in one house, ballroom house and physical house…The ages went anywhere from 13 to about 30…That was the ’90s, so there weren’t many safe spaces to go to, to feel like you were comfortable or be with family or just to feel safe.” Revlon, Ebony, and Dior’e were the primary Baltimore houses in the ‘90s.

I recorded oral histories with Icons in Baltimore’s ballroom scene who told me that a few “pioneers” – among them Tony Revlon and Lisa Revlon – brought ballroom culture from New York City to Baltimore in the 1980s. Lisa Revlon told me that she founded the House of Face in New York, met pioneers like Paris Dupree, and joined the House of Revlon. Ballroom artists from New York City followed her to Baltimore in the 1980s. “We ended up bringing ‘em down here to Baltimore,” she told me, “and they liked it…They was hanging out with us. They started going to the club with us. They already knew we were Revlons.” The Revlons organized a ball at Club Fantasy, Lisa said, “so in essence, I did bring all that madness to Baltimore.”

Alvernian Davis, the founder of the Iconic House of Prestige, told me the House of Revlon “was the first house in Baltimore, even though it was a New York City house. Tony and Stewart, which were the mother and father at the time, they moved out of New York and moved to Baltimore. So they created this whole community of ballroom people down there, which mostly were Revlon members.” Enrique St. Laurent recalled, “It was [the houses of] Face, Revlon, and then other houses just kinda came in [in the 1980s]. So you had houses that were coming from New York, like Ebony. Chanel came in…Houses started coming in, filtering in Baltimore”

Sandy Dior’e told me she founded the House of Dior’e in 1995. “I was the foundation and the blueprint of that,” she said. “And it’s not just in ballroom in Baltimore city, but it’s in outreach I do; it’s in advocacy I do; it’s in helping my community.” In Baltimore, “I don’t believe there’s anyone that can contest to me not being mother or grandmother or auntie.” Monique West told me she joined the House of Dior’e around 1995. “That was the particular family that I belonged to. So it was one apartment just full of people and everybody in there were like family, helping each other get ready, helping each other get whatever they needed for a category.” There were “about 15 people in a one-bedroom apartment,” she recalled. “Everybody was in one house, ballroom house and physical house…The ages went anywhere from 13 to about 30…That was the ’90s, so there weren’t many safe spaces to go to, to feel like you were comfortable or be with family or just to feel safe.” Revlon, Ebony, and Dior’e were the primary Baltimore houses in the ‘90s.

Scene from “Paris is Burning” (1991) the much-criticized documentary about New York City’s ball scene in the 1980s, featuring Willi Ninja, Pepper LaBeija, and Paris Dupree.

Narrators told me that ballroom artists in other cities often perceive Baltimore, a city associated with television shows like The Wire, as the “underdog” of the ballroom world. “We’ve always been considered the underdogs,” Sandy Dior’e told me, “but we always rose to the occasion. Baltimore is a city, to me, with the most realest female figures, with the most talented voguers, with the most beautiful faces, and our runway in ‘realness with a twist’ is just off the chain.” Monique Carter echoed this statement. “We can go to any city and we can beat those people, but . . . we don’t have all of the luxuries that they have.” Baltimore is “the underdog city, so we have to work hard.” New York and Washington D.C., Sebastian Escada told me, “swallow Baltimore up because it’s in the middle . . . but Baltimore is always holding down ballroom.”

Narrators taught me about the non-biological families they create and nurture through ballroom. Marquis Clanton’s ballroom house, the Revlons, “became my family outside of my family, certain stuff that I couldn’t have a conversation with my mother or my father about, I could have with my Revlon family.” Lisa Revlon told me of her house, “They became my extended family. And I don’t wanna use the word ‘extended,’ because they are family. Mothers, grandmothers.” Ballroom transmits cultural knowledge through these kinship networks. “It just passes down,” Monique Carter told me. “That’s why I say in some kind of way we’re like one, big, large family.” Sebastian Escada told me kinship networks provide support. “Ballroom helps to bring [together] people together dealing with different crises in their lives. There are people in ballroom that may have been suicidal. There may have been people in ballroom who were homeless. But when they join these houses, 99 percent of the time, the leaders of the houses connect them with different things outside of ballroom that will help them along with having a productive life.”

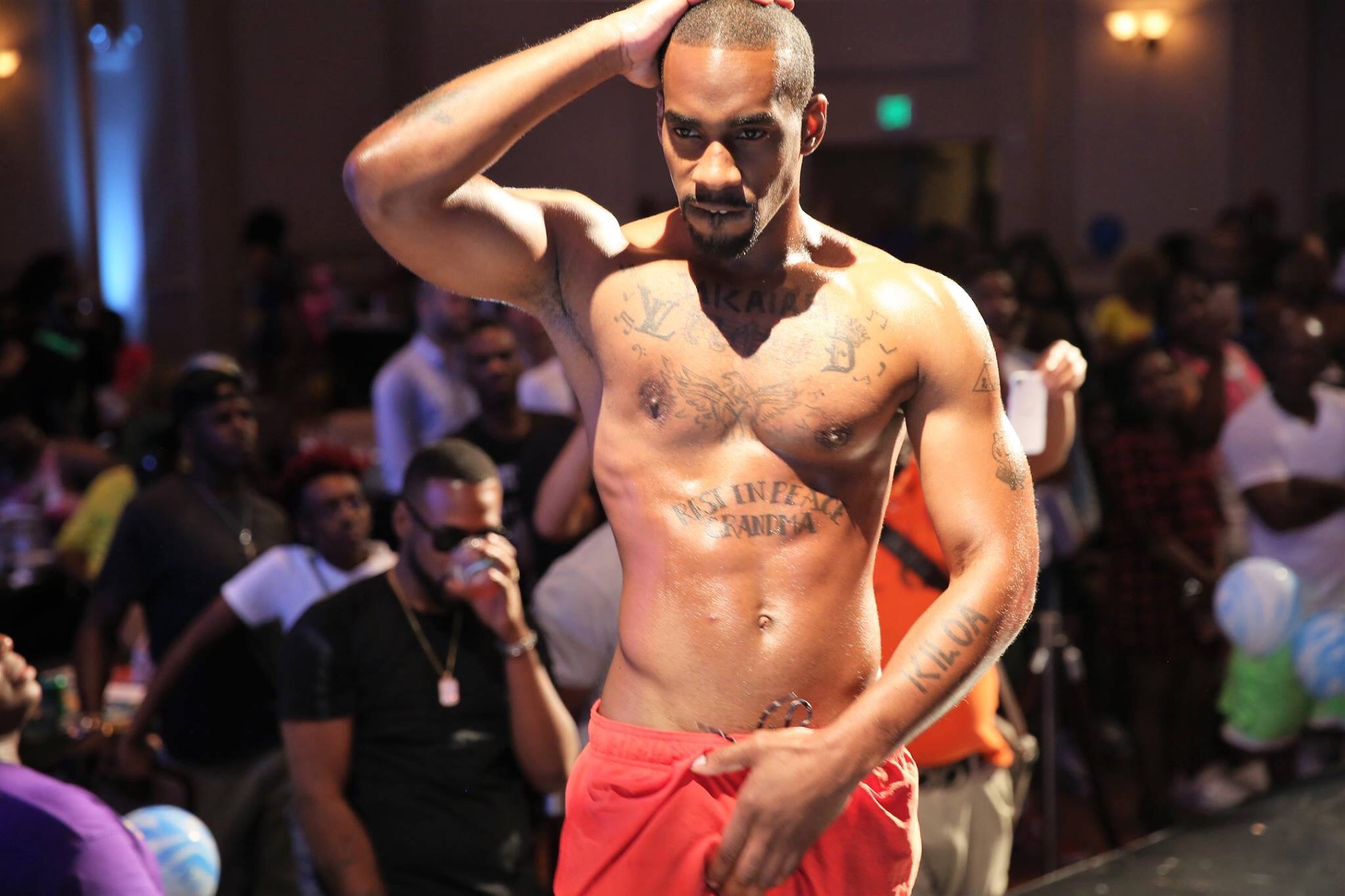

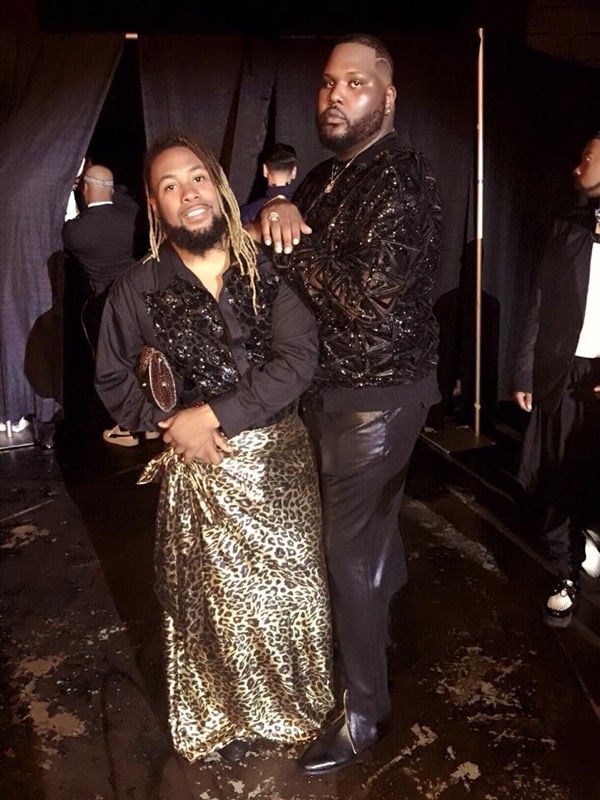

Narrators taught me that performers create new social worlds at ball competitions. Marco West told me a ball “is about creating a fantasy and living it for that night.” Peanut Revlon recalled a category at an under-the-sea ball that required competitors to perform as mermaids. A trans woman, elaborately dressed from head to prosthetic fin, competed while submerged in an oversized tank. Several of her house members wheeled the tank onto the runway. “She had every fish you could name inside this fish tank, and her hair was so long, it came out the fish tank all the way on the floor. . . . To have a person inside of a fish tank, with all this water, crabs, and lobsters . . . it’s like, ‘Wait a minute. What is going on here?’ People still talk about [that] ball.” According to Keith Ebony Holt, “You can be anything you want to be in ballroom.”

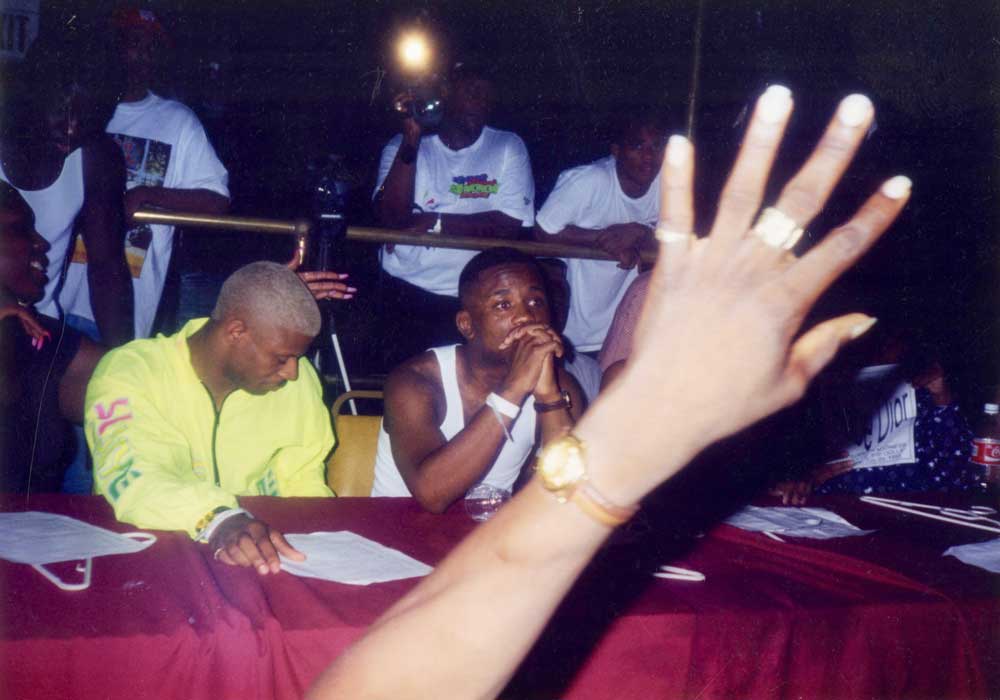

Narrators taught me that ball “commentators,” or masters of ceremonies, are ballroom’s historians. A commentator, as Sandy Dior’e told me, “is a person who controls the ball, is the person that narrates the whole thing. When they go around to different states to states, city to cities, country to country, the people that stood out . . . get acknowledged for their accolades and for what they do.” Monique Carter told me that commentators “have to do their research and keep up on who walks what [category] and remember who won what.” A commentator might ask performers to call forth or embody a past performance. Sebastian Escada told me a commentator may say, “I remember this night. It was a night like this where Octavia, she came from the ceiling. Let’s try to make it a night like that.” Or they might say, “Bring it like Octavia St. Laurent on the same night when she brought in a gown.” A performer might pay homage to a performer by walking the runway in the style of that performer. The commentator will reference history “to make you feel that same energy that happened back then.” They are ballroom’s “true historians, because they have the stories of all the things that have happened at balls.”

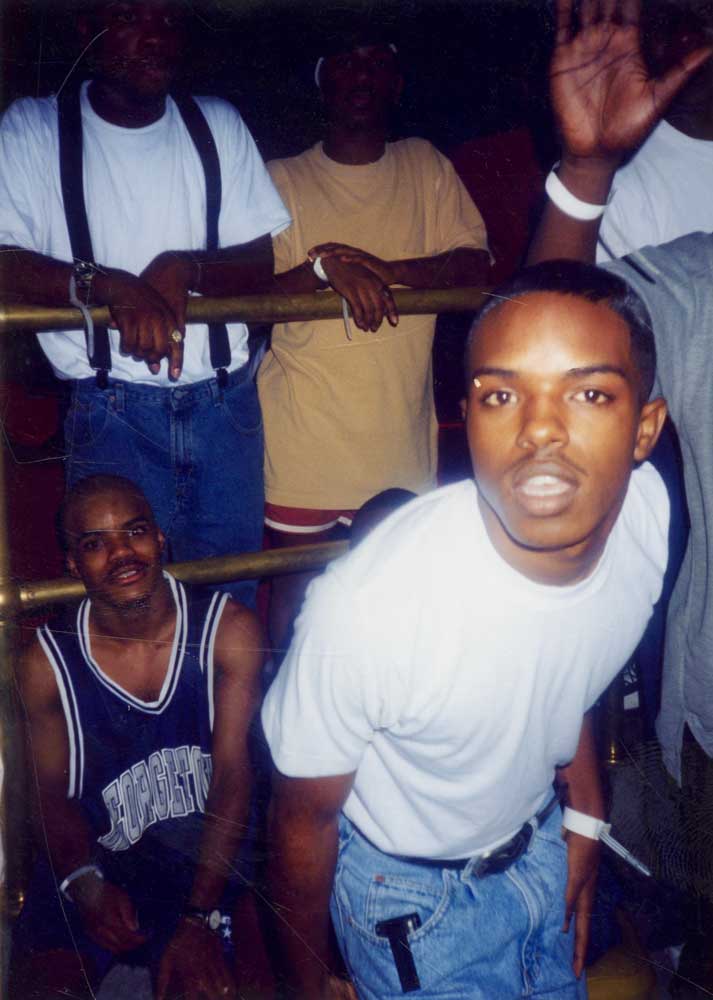

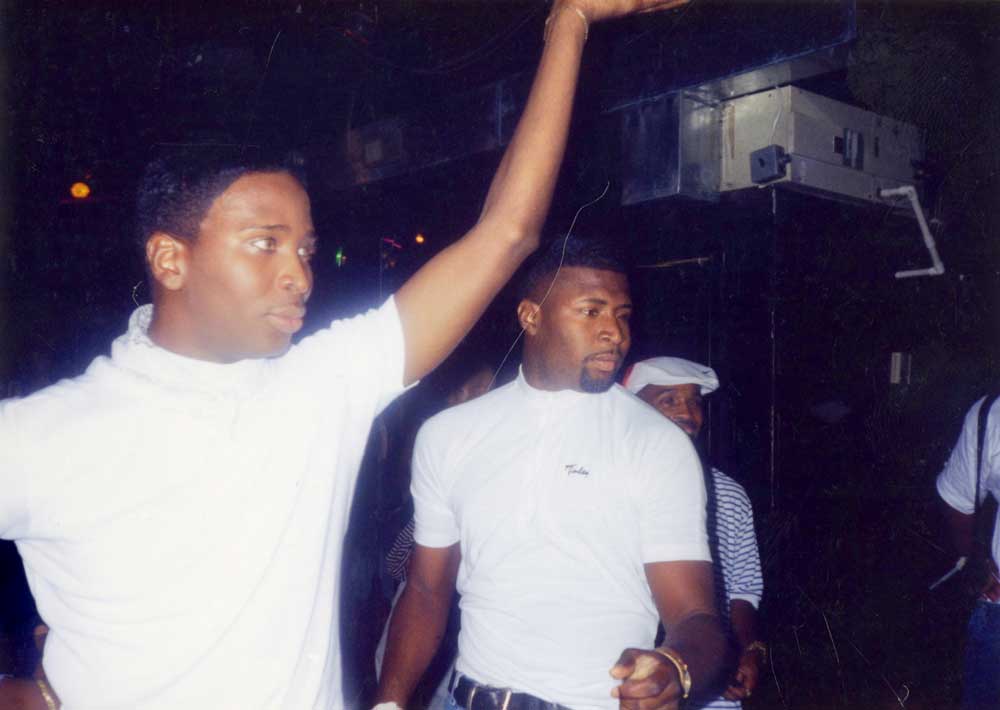

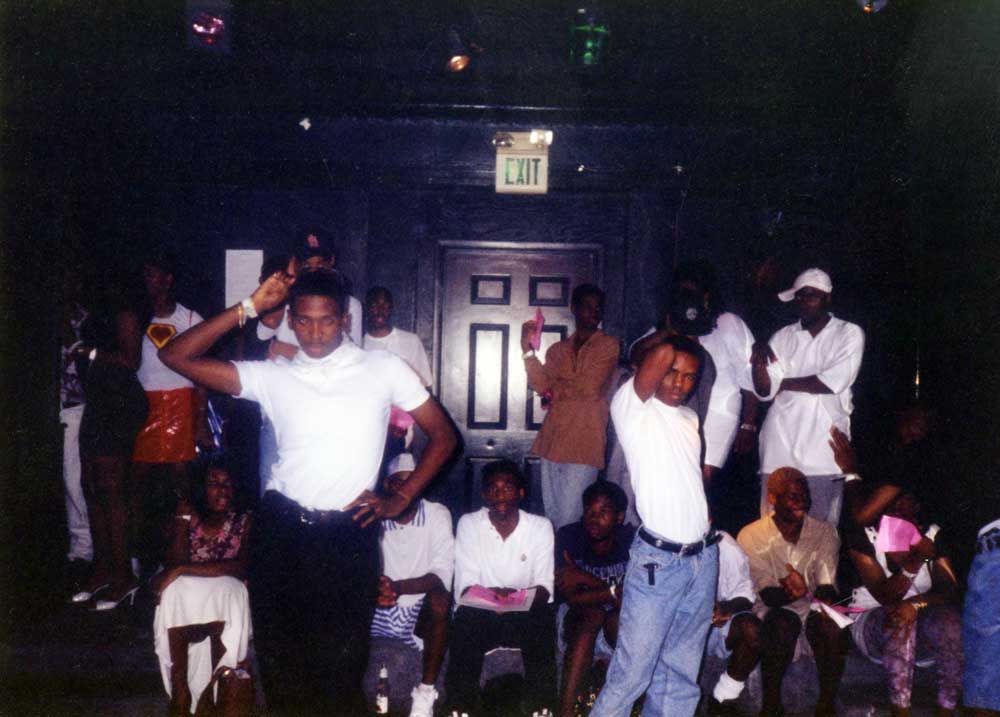

Baltimore’s Club Bunns became a center for the city’s ball culture by the 1990s. View a video from a 2015 ball competition at Club Bunns. The club closed in 2019. According to Boom, a Peabody Ballroom Experience participant, “the clubs are all closed down and a lot of places are not LGBTQ-friendly anymore. We had the Paradox…We had Club Bunns. There was A-list Tuesdays every Tuesday of every month. We had clubs to have balls at, but right now it’s just everything is shutting down. There’s no clubs available.” This said, ballroom artists continue to find venues in which to organize balls, including the George Peabody Library. One of the most consistent elements of ballroom culture is its ability to thrive and survive. According to Twiggy Pucci Garçon, ballroom “has managed to stay alive and well through the drug crisis, the HIV and AIDS crisis, and several presidential crises. It continues to stand on its own as a safe, affirming space for people when they don’t have anywhere else to go, to exist.”

Since its beginnings in Harlem, ballroom culture has expanded to almost every major city in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Latin America. There are ballroom scenes in Chicago; Atlanta; Charlotte, North Carolina; Los Angeles; Baltimore; Berlin; London; and Paris. Ballroom artists belong to houses with members across the globe. Many Baltimore artists regularly travel to Europe to visit their international house members. As such, ballroom has become an international social world connecting far-flung communities. It will continue to evolve and grow.

Photos courtesy of Chronicle Images/Legendary Marco West

Narrators told me that ballroom artists in other cities often perceive Baltimore, a city associated with television shows like The Wire, as the “underdog” of the ballroom world. “We’ve always been considered the underdogs,” Sandy Dior’e told me, “but we always rose to the occasion. Baltimore is a city, to me, with the most realest female figures, with the most talented voguers, with the most beautiful faces, and our runway in ‘realness with a twist’ is just off the chain.” Monique Carter echoed this statement. “We can go to any city and we can beat those people, but . . . we don’t have all of the luxuries that they have.” Baltimore is “the underdog city, so we have to work hard.” New York and Washington D.C., Sebastian Escada told me, “swallow Baltimore up because it’s in the middle . . . but Baltimore is always holding down ballroom.”

Narrators taught me about the non-biological families they create and nurture through ballroom. Marquis Clanton’s ballroom house, the Revlons, “became my family outside of my family, certain stuff that I couldn’t have a conversation with my mother or my father about, I could have with my Revlon family.” Lisa Revlon told me of her house, “They became my extended family. And I don’t wanna use the word ‘extended,’ because they are family. Mothers, grandmothers.” Ballroom transmits cultural knowledge through these kinship networks. “It just passes down,” Monique Carter told me. “That’s why I say in some kind of way we’re like one, big, large family.” Sebastian Escada told me kinship networks provide support. “Ballroom helps to bring [together] people together dealing with different crises in their lives. There are people in ballroom that may have been suicidal. There may have been people in ballroom who were homeless. But when they join these houses, 99 percent of the time, the leaders of the houses connect them with different things outside of ballroom that will help them along with having a productive life.”

Narrators taught me that performers create new social worlds at ball competitions. Marco West told me a ball “is about creating a fantasy and living it for that night.” Peanut Revlon recalled a category at an under-the-sea ball that required competitors to perform as mermaids. A trans woman, elaborately dressed from head to prosthetic fin, competed while submerged in an oversized tank. Several of her house members wheeled the tank onto the runway. “She had every fish you could name inside this fish tank, and her hair was so long, it came out the fish tank all the way on the floor. . . . To have a person inside of a fish tank, with all this water, crabs, and lobsters . . . it’s like, ‘Wait a minute. What is going on here?’ People still talk about [that] ball.” According to Keith Ebony Holt, “You can be anything you want to be in ballroom.”

Narrators taught me that ball “commentators,” or masters of ceremonies, are ballroom’s historians. A commentator, as Sandy Dior’e told me, “is a person who controls the ball, is the person that narrates the whole thing. When they go around to different states to states, city to cities, country to country, the people that stood out . . . get acknowledged for their accolades and for what they do.” Monique Carter told me that commentators “have to do their research and keep up on who walks what [category] and remember who won what.” A commentator might ask performers to call forth or embody a past performance. Sebastian Escada told me a commentator may say, “I remember this night. It was a night like this where Octavia, she came from the ceiling. Let’s try to make it a night like that.” Or they might say, “Bring it like Octavia St. Laurent on the same night when she brought in a gown.” A performer might pay homage to a performer by walking the runway in the style of that performer. The commentator will reference history “to make you feel that same energy that happened back then.” They are ballroom’s “true historians, because they have the stories of all the things that have happened at balls.”

Baltimore’s Club Bunns became a center for the city’s ball culture by the 1990s. View a video from a 2015 ball competition at Club Bunns. The club closed in 2019. According to Boom, a Peabody Ballroom Experience participant, “the clubs are all closed down and a lot of places are not LGBTQ-friendly anymore. We had the Paradox…We had Club Bunns. There was A-list Tuesdays every Tuesday of every month. We had clubs to have balls at, but right now it’s just everything is shutting down. There’s no clubs available.” This said, ballroom artists continue to find venues in which to organize balls, including the George Peabody Library. One of the most consistent elements of ballroom culture is its ability to thrive and survive. According to Twiggy Pucci Garçon, ballroom “has managed to stay alive and well through the drug crisis, the HIV and AIDS crisis, and several presidential crises. It continues to stand on its own as a safe, affirming space for people when they don’t have anywhere else to go, to exist.”

Since its beginnings in Harlem, ballroom culture has expanded to almost every major city in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Latin America. There are ballroom scenes in Chicago; Atlanta; Charlotte, North Carolina; Los Angeles; Baltimore; Berlin; London; and Paris. Ballroom artists belong to houses with members across the globe. Many Baltimore artists regularly travel to Europe to visit their international house members. As such, ballroom has become an international social world connecting far-flung communities. It will continue to evolve and grow.

Photos courtesy of Chronicle Images/Legendary Marco West

Notes and Resources:

Arnold, Emily A. and Marlon M. Bailey. “Constructing Home and Family: How the Ballroom Community Supports African American GLBTQ Youth in the Face of HIV/AIDS,” Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services 21, nos. 2–3 (2009): 171–188.

Bailey, Marlon M. Butch Queens Up in Pumps: Gender, Performance, and Ballroom Culture in Detroit. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013.

Bailey, Marlon M. “Gender/Racial Realness: Theorizing the Gender System in Ballroom Culture,” Feminist Studies 37, no. 2 (2011).

Chauncey, George. Gay New York: The Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940. London: Flamingo, 1995.

hooks, bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Hughes, Langston, 1902-1967. The Big Sea: an Autobiography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1945.

Lawrence, Tim. “Listen and You Will Hear All the Houses: A History of Drag Balls, Houses and the Culture of Voguing,” in Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City, 1989–92, by Chantal Regnault and Tim Lawrence. London: Soul Jazz Books, 2018, 3-10.

moore, madison. Fabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018.

Matthews, Ralph. “31 Debutantes Bow at Local ‘Pansy’ Ball: Men of Neuter Gender Frolic,” Baltimore Afro-American, March 21, 1931, 1.